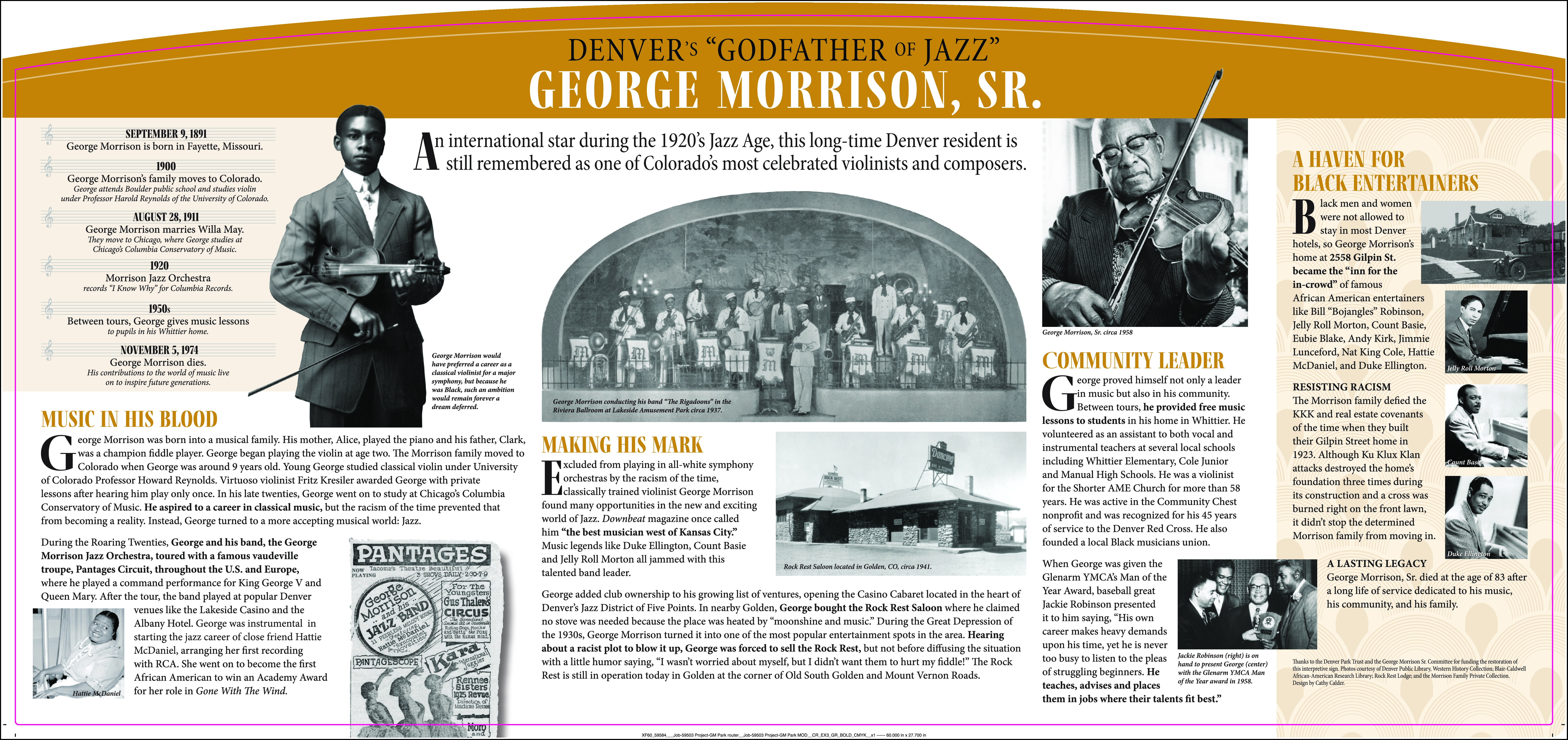

Admirers of George Morrison Sr., of which there are many…

…feel he is to Denver jazz what Louis Armstrong was to the sound of New Orleans. But while Morrison, appropriately referred to as “Denver’s godfather of Jazz,” more than earned this honorific during his distinguished career, his achievements transcend genre and medium. The violinist and composer was a pioneer of all Colorado music during the 20th century as well as a towering social figure whose influence seems to grow with each passing year.

Born in Fayette, Missouri on September 9, 1891, Morrison grew up in a musical household; his mother played piano and his father was a champion on the fiddle. After moving to Boulder with his family as a child, George took violin lessons from a University of Colorado professor. Following his high school graduation and marriage to Willa May of Denver, where he relocated, he continued his classical training at Chicago’s Columbia Conservatory of Music. But since no symphonies of the day would hire Blacks, Morrison pursued a different path as leader of a band specializing in a new musical style: jazz.